Oil palm sector navigates slippery slope

By BHUPINDER SINGH

bhupinder@thestar.com.my

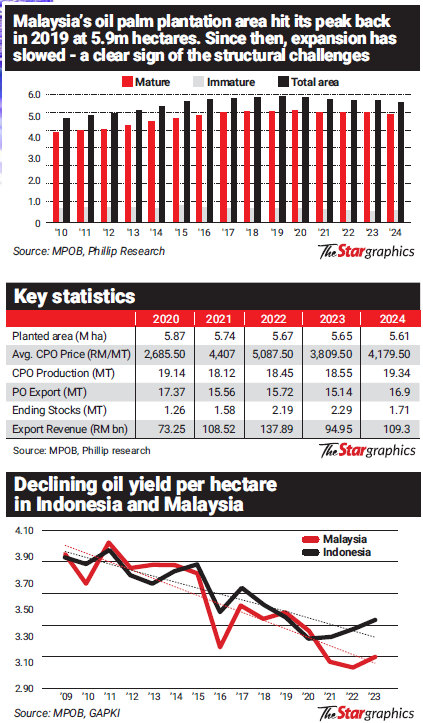

WITH crude palm oil priced at RM4,000 per tonne, upstream palm oil producers are enjoying strong margins, even as they navigate various operational challenges.

Some large planters are shifting more of their production to the spot market instead of forward sales, aiming to capitalise on better prices driven by global market volatility.

However, despite the favourable pricing environment, Malaysia’s upstream oil palm industry is grappling with significant challenges that could impact both the demand-supply dynamics of the edible oil market and the broader local economy.

Ageing oil palm trees and labour shortage, and to some extent bad weather patterns due to climate change, have seen yields fall sharply.

National average crude palm oil (CPO) yields now are at three to four tonnes a ha per annum (despite having advances in agronomy, breeding and technology). This is well below eight to 10 tonnes if fresh fruit bunch (FFB) production is at an optimum 20 to 30 tonnes per ha annually from prime aged trees (eight to 18 years). The yield average has been dragged down by the poor performance of smallholders and some large plantation groups.

The labour shortage, with a deficit of over 40,000 workers, especially harvesters, has caused uncollected fruits and yield loss. This has led to an estimated RM20bil in revenue losses over the past three years, as reported by the Malaysian Palm Oil Association (MPOA).

Lay of the land

Additionally, rising replanting costs and the ganoderma stem rot fungus have exacerbated challenges for Malaysia’s golden crop, impacting around 14% of planted areas. About a third of the 5.6 million ha of oil palm cultivated land in Malaysia, and an equal percentage of the total acreage in Indonesia, will require replanting by 2027.

| The Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) stated as of December 2024, Malaysia has about 9.3% of old trees above 25 years old which are less productive. Old trees should preferably be less than 10% of the total planted area as such trees start becoming less productive and are difficult to harvest because the palms can be above 20 m high. From 2020 to 2024, it notes that the average replanting rate in Malaysia stood at 2.1%, well below the optimum target of 4%. Notably, while private and government agency estates achieved a replanting rate of 2.4%, the rate among independent smallholders was just 0.5%. “This discrepancy has highlighted the need for targeted support for independent smallholders, who face significant barriers to replanting. The government has allocated RM100mil in 2024 and in 2025 to fund a targeted matching grant, specifically to assist independent smallholders, as their low replanting rates present a considerable challenge to the industry’s long-term sustainability,” MPOB director-general Datuk Dr Ahmad Parveez tells StarBiz 7. High CPO prices have contributed to the ageing of local plantations. Since 2020, geopolitical tensions, strong demand from China and India, and Indonesia’s bio-diesel mandate have kept CPO prices above RM3,000 per tonne. At this level, independent smallholders are less motivated to replant. A rush to replant Industry sources estimate some 1.2 million ha will need replanting in Malaysia by 2027. The situation is serious and time-sensitive. Based on MPOB data, over 672,000 ha are above 25 years old and past their prime, with an additional 400,000 ha to 500,000 ha set to reach the same stage by 2027. Old palms (more than 25 years) produce 30% to 40% lower yields, which impacts national CPO output. Additionally, taller or older palms make harvesting more challenging and costly, leading to missed opportunities. “Without replanting, Malaysia could lose up to two million tonnes of CPO annually, worth about RM10bil to RM12bil in export revenue. We urgently need a ‘rush to replant’ programme, targeting at least 150,000 ha 200,000 ha annually over the next five years. “This must be backed by multi-agency coordination, stronger public-private financing and mechanised replanting methods,” Roslin Azmy Hassan, chief executive of MPOA tells StarBiz 7. The replanting will cost a tonne of money. Based on an average per ha cost of RM25,000 (from sapling to production three to four years later), replanting 1.2 million ha could cost the industry some RM30bil. Big plantation companies like SD Guthrie Bhd, IOI Corp Bhd, Kuala Lumpur Kepong Bhd (KLK) and Genting Plantations Bhd have the balance sheets and resources to fund their replanting. Companies like KLK, IOI and Hap Seng Plantations Holdings Bhd have to undertake some heavy replanting as over 25% of their acreages is past their prime, according to reports. Independent smallholders, who account for 14.6% of total planted area or 830,000ha, are at the heart of the problem which can strain the palm oil supply chain. They have delayed replanting as it leads to a loss of income for three to four years. The high CPO price makes the decision even harder as harvesting from older trees can still provide attractive short-term returns. In a low CPO price environment, limited access to financing can constrain their replanting efforts as well. “A purely market-driven solution won’t work for smallholders. We need deliberate policy intervention combining financial incentives, affordable financing schemes and technical support to break this cycle. “Without this, the national replanting effort risks stalling as smallholders control a significant portion of the ageing palms that must be replaced if we want to safeguard national productivity and competitiveness,” says Joseph Tek, a planter with more than three decades in the sector including roles as chief executive officer (CEO) of MPOA, CEO and managing director of IJM Plantations Bhd and president of the Malaysian Estate Owners Association. In Malaysia, only 132,000 ha were replanted in 2023, shrinking further to 114,000 ha in 2024. Persisting with this means progressively declining national productivity, rising costs per tonne and weakening global competitiveness at a time when the industry is already facing external pressures on sustainability, labour and market access. All is not lost yet. “The replanting challenge is manageable – but only if we act decisively and collectively. “A ‘rush to replant’ scheme is not just desirable; it’s essential. Without accelerated replanting, we risk entrenching inefficiency and eroding the economic viability of the sector,” Tek warns. Funding shortfall The government has allocated RM100mil each for 2024 and 2025 under its Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting Financing Incentive Scheme (TSPKS) 2.0 for replanting about 6,000 ha (about RM17,000 a ha) each year. This allocation is aimed at incentivising smallholders to continue replanting unproductive and ageing oil palm trees, with the funding structured as 50% grants and 50% soft loans. At present about 300,000 smallholders manage about 27% of Malaysia’s total 5.7 million ha of oil palm plantations. They typically own or manage less than 40 ha (100 acres). So while the RM100mil shows intent, the challenge is multiple times bigger. Roslin says the government needs to scale up TSPKS to at least RM500mil annually and improve the matching grant mechanism for smallholders and mid-size estates. He says the upstream sector’s current problems need a staggered approach. In the short-term MPOA urges the acceleration in foreign labour approvals and incentivise mechanisation in harvesting and field upkeep. For the medium-term, it calls for incentives such as tax reliefs, matching grants and loan subsidies for replanting. Over the long-term, Roslin suggests setting up a national replanting fund, and the development of scalable mechanisation solutions and encouraging sustainability-linked financing mechanisms. Indonesia funds its replanting through a Palm Oil Fund financed by export levies on CPO which provides a larger and more sustainable financial base for replanting. Tek calls for targeted government incentives and soft loans – perhaps through replanting grants, tax breaks, reinvestment allowance or subsidised financing to lower the upfront burden. He says pooling industry resources via CPO windfall profit levy or industry levies be temporarily redirected to a national replanting fund as well as public-private partnership models where financial institutions, government and plantation companies collaborate to structure affordable long-term financing. “This is not just a plantation management issue – it is a national competitiveness issue. We can manage it, but only if we stop deferring action and commit to a coordinated, well-financed replanting drive, starting now,” he says. Tek adds that the fiscal burden on the industry should be reviewed and addressed. The sector is already heavily taxed; rather than adding to this, policy support should aim at promoting reinvestments enabling replanting, mechanisation and sustainability efforts, so that Malaysia’s oil palm sector can remain productive, resilient and globally competitive. To break the industry’s dependency on manual labour, Tek calls for accelerated adoption of mechanisation as well as designing estates during replanting to be machine-friendly so that mechanisation can succeed. MPOB, which regulates and coordinates activities related to the oil palm industry, including licensing, enforcement and research, says the development of mechanisation is progressing steadily, particularly in tackling the challenges associated with harvesting of FFB from older and taller palms. “A key initiative driving this progress is the Mechanisation and Automation Consortium for Oil Palm (MARCOP), a collaborative platform spearheaded by industry representatives, in conjunction with related government agencies, and administered by MPOB. MARCOP is focused on developing commercial-ready prototypes based on previous research and development (R&D) outcomes, to deliver scalable solutions that can be adopted industry-wide,” Ahmad Parveez says. At the same time, it continues to conduct R&D on a variety of prototype harvesting machines, particularly those designed to access high-reach palms more effectively. These innovations are intended to increase productivity, reduce reliance on manual labour, and enhance harvesting efficiency in mature plantations, he adds. Production to rise Malaysia and Indonesia’s lid on opening new land for new acreages means production growth is expected to be in single-digit levels in the medium term with Malaysia’s total CPO production forecast to hit 19 million tonnes in 2025. For January to May, Malaysia’s total CPO production is estimated at seven million tonnes. Phillip Research, in a recent plantation sector report, notes exports are projected to grow at a modest 0.9% year-on-year to 17.1 million tonnes in 2025, supported by restocking in the second half of 2025 (2H25) and broader market diversification into emerging markets. Its in-house forecast for CPO price is to average RM4,100 per tonne in 2025 and ease slightly to RM4,000 a tonne in 2026. Akash Gupta, director at Fitch Ratings, expects CPO prices to gradually weaken in 2H25 on improving output due to favourable weather conditions. He adds that CPO prices are currently competitive with soyoil which should prevent a sharp drop in prices. He is unsure how the trade war and outcome of trade negotiations will impact CPO buyers like China and India. “It is unclear whether India and China will increase purchases of American soybean and soyoil at the expense of CPO. “India has been a price-sensitive market and CPO prices are currently competitive. China has adopted an assertive approach towards the United States in trade negotiations so far,” he explains. On the issue of ageing acreage profiles in Indonesia and Malaysia, he says larger companies such as SD Guthrie Bhd have been investing in replanting in recent years with newer variety seeds to improve their plantation yield profile. “Nonetheless, industry-wise replanting has been slow. “Additionally, oil palm acreage growth has stalled due to Indonesia’s moratorium and subsequent slowdown in issue of new permits under former President Jokowi. “Prabowo has adopted a more favourable stance, but this is unlikely to have an impact in the next four to five years. “These factors should constrain output growth, which we expect to be driven by better-yielding seed varieties,” he says. Phillip Research says the plantation sector’s valuations are fair and structural headwinds cap upside. The local plantation sector trades at 15 times forward price earnings multiple, well below its 10-year mean of 31.3 times and near its -0.5SD level of 19.3 times. The valuation de-rating reflects persistent structural concerns, rising EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) compliance costs, and muted investor sentiment. Malaysia’s classification as a “standard-risk” country under the EUDR continues to weigh on export margins. AmResearch adds that although the Malaysian Palm Oil Council is challenging the EU’s benchmarking methodology, the impact on large Malaysian palm exporters is not expected to be significant as they are prepared for the EUDR and have been sending trial shipments of EUDR-compliant palm products. |

Comments ( 4 )